Nuclear Power: Obama Calls It Right

As is reported about everywhere, President Obama has announced real support for a nuclear power infrastructure redux in the United States. Here in the past [1] [2] [3], I've been an advocate of nuclear power. My position has not changed. Skimming thru some of the recent articles, I have found some select, encouraging remarks about nuclear power. For example,

The US Department of Energy says that coal-fired power plants (burning anthracite, bituminous, subbituminous, lignite, waste coal, and coal synfuel) generated 1,787,669,000 megawatthours in the rolling 12-months ended October 2009, while natural gas-fired plants accounted for 906,217,000 megawatthours, and petroleum liquids (distillate fuel oil, residual fuel oil, jet fuel, kerosene, and waste oil) generated 28,216,000 megawatthours. Nuclear plants generated 906,217,000 megawatthours in the same period. [Amir Adnani, an energy industry executive] says, "These figures are astonishing because, if the US were to use as much nuclear energy as France, which relies on nuclear power for 80% of its electricity, we could shut down virtually every coal, natural gas-fired and oil-burning power plant. Our greenhouse gas emissions would plummet, our national security would be enhanced, and our balance of payments situation would improve."[4]The U.S. has no shortage of Uranium either, as the stuff is "literally under our feet." Although we import approximately 95% of the uranium we use, the US has the fourth largest deposits of uranium in the world.[4]

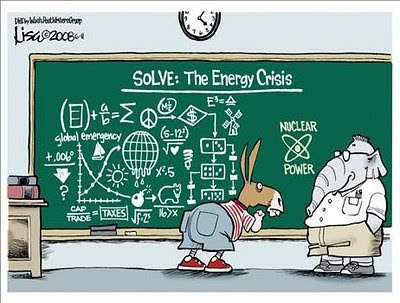

Although I think the Democrats have been both wise and prudent to emphasize and pursue other sources of energy, I've always felt that nuclear power is the most efficient, immediate, and global-warming friendly solution to world energy needs. It also heartens me that well-informed scientists think this too.[5][6] Politically, as the both-isle standing and clapping ritual showed during Obama's speech, the Republicans can support this. Solid science, correct technology, presidential priority,and bi-partisan agreement makes this the best news I've heard in a long time about the U.S.'s energy future.

O.

REFERENCES

[1] "Nuclear Power's Hour is Now" November 30, 2008.

[2] "Coal Plants and U.S. Electricity" May 16, 2009

[3] "Steven Chu, the right choice for secretary of energy" December 11, 2008 (Chu is supportive of the nuclear option too. Obama can finally turn him loose on the problem he's been desperately wanting to attack.)

[4] "Obama: Nuclear Power Part of America's Energy Future" Zibb -- Business Wire (Accessed Jan 28, 2009)

[5] "Can nuclear power compete?" Scientific American Dec. 9, 2008 (Accessed Jan. 28, 2010)

[6] John M. Deutch and Ernest J. Moniz "The Nuclear Option (.PDF)" Scientific American. (Accessed Jan 28, 2010)

Labels: Energy Policy, Nuclear Power